By Norman (Otis) Richmond

By Norman (Otis) RichmondToronto--After many years of phone conversations, emails and messages fromrelatives and friends I finally met Boots Riley. Riley is the face of thehip-hop crew, the Coup, along with Pam “The Funktress,” who was unable tomake the trip to Toronto for the Coup’s recent debut performance here atthe Reverb.

Despite driving himself, a three piece band and one backupvocalist/rapper, Riley and crew were more than able to please the crowd asthey breezed though tracks from their catalogue of CDs, which includesParty Music, Steal This Album, and Genocide & Juice. They also performedseveral tracks from their forthcoming CD, Picka Bigger Weapon. “MyFavorite Mutiny” and “Baby Let’s Make a Baby” were well received by theToronto crowd. “My Favorite Mutiny,” which features Black Thought (fromthe Roots) and Talib Kweli, heated up the spot. “Me & Jesus The Pimp In A79 Granada Last Night” and other tracks rocked the house.

However, the real crowd pleaser was Boots a cappella rendition of “TheUnderdog.” The group was forced to do an encore and they pleased theiraudience with “Ghetto Manifesto” and “Wear Clean Draws” which Bootsdedicated to his daughter. The Coup’s band sounded like Larry Graham (ofthe group Sly & The Family Stone) on bass, Jimi Hendrix (world’s mostinfluential guitarist) on guitar, and Earl Young (MFSB) on drums. Themusicians in the Coup band are Quebec Jackson, Drums; Riccol Johnson,Bass; and Steve Wyreman, Guitar. Silk-E is the vocalist/rapper with the group.

We caught up with Riley before the performance. The interview wasconducted as Riley drove himself to his hotel in Mississauga to come backand do his show. The Coup’s new CD Picka Bigger Weapon was discussed. The new album features a wide range of artists like Jello Biafra, dead prez,and members from the Parliament and the Gap Band. Riley spoke to us abouteverything from Hip Hop and politics to Katrina and Kanye West to the caseof Crip co-founder Stanley Tookie Williams.

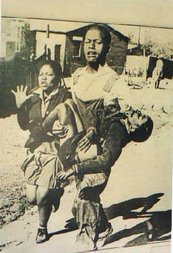

Williams is The San Quentin inmate who was nominated for the 2001 NobelPeace Prize by a member of the Swiss Parliament. Williams, now 47, wassentenced to death in 1981 for four robbery-related murders.

The Crips, a notorious youth street organization (gang), which he and afriend started in South Central Los Angeles in 1971, spread to citiesthroughout the United States and Canada. Copycat gangs would soon crop upin South Africa and Switzerland. Williams experienced a reawakening in1993 and has since attempted to turn his life around. He's written TookieSpeaks Out Against Gang Violence, a series of eight readers aimed at urbanyouth, and Life in Prison, a biography detailing the isolation and despairof death row. He has done this in collaboration with his editor, BarbaraCottman Becnel, detailing the isolation and despair of death row.

The Sundance and Cannes Festival recognized 'Redemption', 2004 TV moviefilmed in Toronto, Canada and based on William’s life story featured astellar cast, including Jamie Foxx starring as the former Crips gangleader, 'Thin Line Between Love And Hate' actress Lynn Whitfield playingthe co-author of William’s books Barbara Becnel, and Canadian Hip-Hopforefather Maestro as former Crips lieutenant turned "Tookie Protocol ForPeace" ambassador.

Riley said that the climate is such that the right-wing Governor ofCalifornia, Arnold Schwarzenegger, could go ahead with December 13thexecution of Williams. Jamie Foxx, Danny Glover and Snoop Dogg have allcalled for Williams not to be executed.

Riley was excited that Melvin Van Peeples wants to produce the Coup’s next video. He says Van Peebles heard the track “We Are The One’s” and lovedthe story, adding that Van Peebles, father of Mario Van Peebles, bestknown as the director of Sweet Sweetback’s Baad Asssss Song, was soimpressed that he agreed not to be too rigid on the price of production.

This is not the first time that a successful Hollywood personality hasworked with the Coup. Roger Guenveur Smith who has acted in most of SpikeLee’s films produced Me And Jesus The Pimp In A 79 Granada Last Night.Back in 1999 the African Liberation Month Coalition and CKLN-FM 88.1screened the video of Me and Jesus the Pimp In A 79 Granada Last Nightalong with the Murder of Fred Hampton.

Riley feels we cannot trust the system because, at its core, it’s designedto exploit people. Over the past few years, U.S. imperialism has uppedthe ante, he says, adding that we need to do is be strategic and targetcompanies and their subsidiaries that do business or have any sort ofconnection to the war effort. We need to shut them down, he says.

The Chicago-born rapper said that he is impressed the many of the newflock of hip hop artists. He spoke about the fact that while 50 Centmaybe hot at the moment, in reality he is not selling tons of units. Rileybelieves it is in the interest of the system to promote the “Get Rich OrDie Tryin’” school of thought. According to Riley artists like dead prez,Mos Def, Talib Kweli, Common and Kanye West are examples of the new breed of hip hop.Toronto-based journalist and radio producer Norman (Otis) Richmond can beheard on Diasporic Music, Thursdays, 8 p.m.-10 p.m., Saturday MorningLive, Saturdays, 10 a.m.-1 p. m. and From a Different Perspective,Sundays, 6-6:30 p.m. on CKLN-FM 88.1 and on the internet at www.ckln.fm/. He can be reached by phone at 416-595-5068 ext 2372 or by e-mail at Norman@ckln.fm.

Monday, December 4, 2006

Saturday, December 2, 2006

Meeting Jean Carne

I have always been a huge fan of Jean Carne. I had the pleasure of meeting Ms. Carne for the first time after admiring her work since the early seventies. More on this meeting soon.

I will soon post an article on Ms. Carne.

I will soon post an article on Ms. Carne.

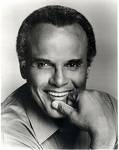

Harry Belafonte

By Norman (Otis) Richmond

Harry Belafonte continues to be in the vanguard of Black artists who stand on the side of the oppressed. Belafonte is featured in Spike Lee’s new documentary When The Levees Broke:A Requiem In Four Acts. He also gave a thought- provoking interview to the BBC. The LIMERS e-group recently had a fruitful discussion about this dialogue.

“The artist elects to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice!I had no alternative!” was the immortal Paul Robeson’s mantra. Who was Robeson,It is the same for Belafonte. I have always had the greatest respect for Belafonte. Both were shining examples of Pan-Africanism and internationalism. He has been a bridge connecting African people from home and aboard. It was Belafonte who arranged for members of the Student Non- Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to visit the freshly independent West African nation of Guinea. He felt they were on the verge of burning out and he wanted to prevent this.

Belafonte is the closest example to Robeson who was his role model. Belafonte like Robeson before him realized that art and culture are weapons in a people’s struggle to exist with dignity, and peace. Robeson paid the supreme price for his stance against U.S. imperialism and global white supremacy. Robeson’s income dipped from $100,000 a year to a mere six thousand a year. Belafonte never the less still held up Robeson as his model for political and artistic excellence. Robeson was a friend of the Caribbean and Africa. He played in Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago, was published in the Jamaican Gleaner and was Afro-Centric before it came in vogue.

Belafonte like his main man understands that “Blackness is necessary but not sufficient”. He is pro-Cuba, pro-Venezuela and stands with working people around the planet. In the 20th century Robeson was called “The tallest tree in the forest.” In the 21st century this applies to the first artist to have a platinum album - Belafonte.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. pointed out in his volume Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Man, “The album Harry Belafonte – Calypso, released at the end of 1956,ended up selling more than a million and a half copies, more than any single artist album ever had before, and it remained on the charts for a year a half. Elvis and Sinatra were big in 1957, yet Belafonte – the King of Calypso, as he was touted – outsold both of them. (With fetching modesty, Belafonte told one reporter, “I don’t want to be known as a guy who put the nail in the coffin of rock and roll”)

Sam Cooke was the most important soul singer in history -- he was also the inventor of soul music, and its most popular and beloved performer in both the black and white

communities. Equally important, he was among the first modern black performers and composers to attend to the business side of the music business, and founded both a record label and a publishing company as an extension of his careers as a singer and composer. Yet, those business interests didn't prevent him from being engaged in topical issues, including the struggle over civil rights, the pitch and intensity of which followed an arc that paralleled Cooke's emergence as a star -- his own career bridged gaps between black and white audiences that few had tried to surmount, much less succeeded at doing, and also between generations; where Chuck Berry or Little Richard brought black and white teenagers together, James Brown sold records to white teenagers and black listeners of all ages, and Muddy Waters got young white folkies and older black transplants from the South onto the same page, Cooke appealed to all of the above, and the parents of those white teenagers as well -- yet he never lost his credibility with his core black audience.

considered Belafonte as one of his role models. Cooke admired Belafonte’s militancy, his business acumen and his ability to crossover into the lucrative Euro-American pop market without compromising his blackness. While still a member of the gospel group the Soul Stirrers he told fellow group member Paul Foster, “I want to be like (him).” He made this statement while pointing at a photo of Belafonte, whose calypso –flavoured “Banana Boat Song (Day-O) was on the current Top Ten. Belafonte’s success was not applauded in all quarters. Daiann McLane a calypso scholar – and singer took Belafonte on. McLane was unimpressed by Belafonte; he referred to his music as “calypso with a conk.” Calypso purist problem with Belafonte was that he was too much of a singer and not a calysionian at all. While Belafonte and Sidney Poitier are best friends they have been known to duke it out from time to time. Poitier said this about his “key spare”. “He (Harry) can be the worst S.O.B. that God ever created. Harry Belafonte will do you in, up, down, and crossways in a minute. You’ve got to be terribly special to him to be excluded from his guillotine when he’s out for blood. But if he’s there for you, he’s there for you all the way.”

Belafonte’s image as the “King of Calypso” was the creation of the media. He has gone to great length to explain that he had no control over how RCA records promoted him, and has conceded that he wasn’t really a calypso singer. However, the S.O.B. in Belafonte has gone on record and said, “I’ll tell you, though, that I find that most of the culture coming out of Trinidad among calypso singers is not in the best interest of the people of the Caribbean community.”

“I think that it’s racist, because you sing to our own denunciation on color. You sing about our sexual power, and our gift of drinking, and rape, and all the things we do to which I have, and want, no particular claim. What I have sought to do with my art is take my understanding of the region and put it before people in a positive way. And doing these songs gives people another impression than the mythology they have that we’re all lazy, living out of a banana tree, fucking each other to death.”

Robeson came into conflict with many African nationalist and Pan-Africanist for some of his film roles. Though Robeson publicly disowned Sanders of the River, Marcus Garvey, the outspoken Jamaican nationalist, still denounced the actor for "pleasing England by the gross slander and libel of the Negro". Belafonte did not wish to be criticised by his brethen and sistren over this issue. He took a hard-line on the film roles he accepted.

He turned down roles in Porgy and Bess, To Sir With Love and Lilies of the Field. He

explained to Gates why he turned down the role in Lilies of the Field, “When I read Lilies of the Field, I was furious. You’ve got these nuns fleeing Communism, and out of nowhere is this black person who throws himself whole- heartedly into their service, saying nothing and doing nothing except being commanded by these Nazi nuns. He didn’t kiss anybody, he didn’t touch anybody, he had no culture, he had no history, he had no family, and he had nothing. I just said, ‘No, I don’t want to play pictures like that.’ What happened was Sidney (Poitier) stepped in – and got the Academy Award.”

Belafonte has pointed out that he and Poitier were both influenced by Robeson. However, “Belafonte points out without bitterness, ‘In the early days, Sidney participated in left affairs, but once he became anointed he gave it up,”

The great African American director/actor Ivan Dixon told this writer that Robeson had consulted both Belafonte and Poitier to not let the system destroy them like they did him. Belafonte apparently didn’t listen as attentively as Poitier and took many risks by publicly attacking injustice world –wide. Belafonte was Martin Luther King’s chief fund-raiser. King summed up the position that all progressives including Belafonte came to believe, “Injustice anywhere, is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Norman (Otis) Richmond can be contacted by e-mail Norman@ckln.fm

Harry Belafonte continues to be in the vanguard of Black artists who stand on the side of the oppressed. Belafonte is featured in Spike Lee’s new documentary When The Levees Broke:A Requiem In Four Acts. He also gave a thought- provoking interview to the BBC. The LIMERS e-group recently had a fruitful discussion about this dialogue.

“The artist elects to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice!I had no alternative!” was the immortal Paul Robeson’s mantra. Who was Robeson,It is the same for Belafonte. I have always had the greatest respect for Belafonte. Both were shining examples of Pan-Africanism and internationalism. He has been a bridge connecting African people from home and aboard. It was Belafonte who arranged for members of the Student Non- Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to visit the freshly independent West African nation of Guinea. He felt they were on the verge of burning out and he wanted to prevent this.

Belafonte is the closest example to Robeson who was his role model. Belafonte like Robeson before him realized that art and culture are weapons in a people’s struggle to exist with dignity, and peace. Robeson paid the supreme price for his stance against U.S. imperialism and global white supremacy. Robeson’s income dipped from $100,000 a year to a mere six thousand a year. Belafonte never the less still held up Robeson as his model for political and artistic excellence. Robeson was a friend of the Caribbean and Africa. He played in Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago, was published in the Jamaican Gleaner and was Afro-Centric before it came in vogue.

Belafonte like his main man understands that “Blackness is necessary but not sufficient”. He is pro-Cuba, pro-Venezuela and stands with working people around the planet. In the 20th century Robeson was called “The tallest tree in the forest.” In the 21st century this applies to the first artist to have a platinum album - Belafonte.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. pointed out in his volume Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Man, “The album Harry Belafonte – Calypso, released at the end of 1956,ended up selling more than a million and a half copies, more than any single artist album ever had before, and it remained on the charts for a year a half. Elvis and Sinatra were big in 1957, yet Belafonte – the King of Calypso, as he was touted – outsold both of them. (With fetching modesty, Belafonte told one reporter, “I don’t want to be known as a guy who put the nail in the coffin of rock and roll”)

Sam Cooke was the most important soul singer in history -- he was also the inventor of soul music, and its most popular and beloved performer in both the black and white

communities. Equally important, he was among the first modern black performers and composers to attend to the business side of the music business, and founded both a record label and a publishing company as an extension of his careers as a singer and composer. Yet, those business interests didn't prevent him from being engaged in topical issues, including the struggle over civil rights, the pitch and intensity of which followed an arc that paralleled Cooke's emergence as a star -- his own career bridged gaps between black and white audiences that few had tried to surmount, much less succeeded at doing, and also between generations; where Chuck Berry or Little Richard brought black and white teenagers together, James Brown sold records to white teenagers and black listeners of all ages, and Muddy Waters got young white folkies and older black transplants from the South onto the same page, Cooke appealed to all of the above, and the parents of those white teenagers as well -- yet he never lost his credibility with his core black audience.

considered Belafonte as one of his role models. Cooke admired Belafonte’s militancy, his business acumen and his ability to crossover into the lucrative Euro-American pop market without compromising his blackness. While still a member of the gospel group the Soul Stirrers he told fellow group member Paul Foster, “I want to be like (him).” He made this statement while pointing at a photo of Belafonte, whose calypso –flavoured “Banana Boat Song (Day-O) was on the current Top Ten. Belafonte’s success was not applauded in all quarters. Daiann McLane a calypso scholar – and singer took Belafonte on. McLane was unimpressed by Belafonte; he referred to his music as “calypso with a conk.” Calypso purist problem with Belafonte was that he was too much of a singer and not a calysionian at all. While Belafonte and Sidney Poitier are best friends they have been known to duke it out from time to time. Poitier said this about his “key spare”. “He (Harry) can be the worst S.O.B. that God ever created. Harry Belafonte will do you in, up, down, and crossways in a minute. You’ve got to be terribly special to him to be excluded from his guillotine when he’s out for blood. But if he’s there for you, he’s there for you all the way.”

Belafonte’s image as the “King of Calypso” was the creation of the media. He has gone to great length to explain that he had no control over how RCA records promoted him, and has conceded that he wasn’t really a calypso singer. However, the S.O.B. in Belafonte has gone on record and said, “I’ll tell you, though, that I find that most of the culture coming out of Trinidad among calypso singers is not in the best interest of the people of the Caribbean community.”

“I think that it’s racist, because you sing to our own denunciation on color. You sing about our sexual power, and our gift of drinking, and rape, and all the things we do to which I have, and want, no particular claim. What I have sought to do with my art is take my understanding of the region and put it before people in a positive way. And doing these songs gives people another impression than the mythology they have that we’re all lazy, living out of a banana tree, fucking each other to death.”

Robeson came into conflict with many African nationalist and Pan-Africanist for some of his film roles. Though Robeson publicly disowned Sanders of the River, Marcus Garvey, the outspoken Jamaican nationalist, still denounced the actor for "pleasing England by the gross slander and libel of the Negro". Belafonte did not wish to be criticised by his brethen and sistren over this issue. He took a hard-line on the film roles he accepted.

He turned down roles in Porgy and Bess, To Sir With Love and Lilies of the Field. He

explained to Gates why he turned down the role in Lilies of the Field, “When I read Lilies of the Field, I was furious. You’ve got these nuns fleeing Communism, and out of nowhere is this black person who throws himself whole- heartedly into their service, saying nothing and doing nothing except being commanded by these Nazi nuns. He didn’t kiss anybody, he didn’t touch anybody, he had no culture, he had no history, he had no family, and he had nothing. I just said, ‘No, I don’t want to play pictures like that.’ What happened was Sidney (Poitier) stepped in – and got the Academy Award.”

Belafonte has pointed out that he and Poitier were both influenced by Robeson. However, “Belafonte points out without bitterness, ‘In the early days, Sidney participated in left affairs, but once he became anointed he gave it up,”

The great African American director/actor Ivan Dixon told this writer that Robeson had consulted both Belafonte and Poitier to not let the system destroy them like they did him. Belafonte apparently didn’t listen as attentively as Poitier and took many risks by publicly attacking injustice world –wide. Belafonte was Martin Luther King’s chief fund-raiser. King summed up the position that all progressives including Belafonte came to believe, “Injustice anywhere, is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Norman (Otis) Richmond can be contacted by e-mail Norman@ckln.fm

When the Panthers and the League Were in Vogue

By Norman Otis Richmond

Mumia Abu-Jamal's latest work, We Want Freedom: A Life in The Black

Panther Party (South End Press, 2004), made me reflect on my political life.I came of age, politically, about the same time as Abu-Jamal. I participated in forming several organizations in the 1960s and '70s. One,the Detroit-based League of Revolutionary Black Workers, while not as well known as the Black Panther Party (BPP), was just as important. One of Abu-Jamal's quotes made me pause and take a deep breath because it hit the

nail on the head.

He writes: "To the average Panther, even though he worked daily in the ghetto communities of North America, his thoughts were usually on

something larger than himself. It meant being part of a worldwide movement against U.S. imperialism, White supremacy, colonialism and corrupting capitalism. We felt as if we were part of the peasant armies of Vietnam,the fedayeen in Palestine, the students strumming in the streets of Paris,and the disposed of Latin America."

I can remember being laughed at by some small-minded people because they felt I identified too much with Africa. My mother used to call me whenever Ho Chi Minh of Vietnam or Mao Zedong of China came on the news by saying,"Norman, your president is on television."

El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz's (Malcolm X) "Message to the Grassroots"

speech had a profound impact on my worldview. This speech was released on an album shortly after his death in the mid-1960s. When Malcolm talked about Afghanistan, Algeria, Burma, the Congo, Cuba, Pakistan, India, Indonesia, Kenya and Korea, I wanted to know everything about those far away places. During this same speech he went on to discuss the French and Russian Revolutions. I began to wonder: "Why don't they teach us about these places and events in school?"

The conditions of African people in the North and the South of the United States made me, and many of my peers, rage. We also discovered that millions of other Africans all over the world were in the same boat. While Abu-Jamal joined the BPP, I became a member of the League. The BPP and the League had many things in common, as well as some significant differences. The League's leadership, like the BPP, embraced Marxism-Leninism,Internationalism and Pan-Africanism; while most of the rank and file embraced revolutionary nationalism. However, the leadership of both groups and the rank and file shared a mutual hatred of U.S. Imperialism. The League addressed the question of cultural nationalism. The BPP and the

League were like political Siamese twins on this question. Both maintained that Blackness was necessary but not sufficient. While both organizations were fiercely internationalist, they differed on which class would lead the Black revolution. Both groups had films about their activities and both came up short on their treatment of women.

Both opposed the Vietnam War. In 1971, when Huey P. Newton, co-founder of the BPP was released from prison in California, his first act was to offer troops to fight in Vietnam on the side of the Vietnamese people. On August 29, 1970 Newton wrote “In the spirit of international revolutionary solidarity the Black Panther Party hereby offers to the National Liberation Front and Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam an undetermined number of troops to assist you in you fight against American imperialism. It is appropriate for the Black Panther Party to take this action at this time in recognize of the fact that your struggle is also our struggle, for we recognize that our common enemy is the American imperialist who is the leader of international bourgeois

domination.”

When General Baker, a central leader of the League, was drafted in 1964 he refused to heed Uncle Sam's call and created a lot of drama for the ruling elite. First, he wrote a letter to the draft board denouncing the war. Then, the organization he had belonged to before joining the League decided to protest his induction. They put out leaflets and press announcements stating that 50,000 Blacks would show up at the Wayne County Induction Center when Baker had to report. Only eight demonstrators were there, but the threat of mass action had convinced the U.S. army to find Baker "unsuitable" for service. Baker's position became the League's.

While the BPP held the lumpen proletariat up as the leaders of the Black revolution, the League maintained the Black working class was the natural leaders or vanguard of that struggle. The lumpen proletariat (directly translated: rag-proletariat) - a term used by Marxists - included prostitutes, beggars and homeless people.

Both groups were the subjects of films. Mario and Melvin Van Peebles'

film, Panther, was a fairer treatment of the group than most expected. The League's film, Finally Got The News, was a major breakthrough. While others created most of the films about the BPP, the League had complete control of Finally Got The News. John Watson, a central leader of the group, was largely responsible for this film.

How did women fare in the BPP and the League? On this question the BPP came out better than the League. The BPP at least had women on their central committee. The League had none. Marian Kramer, the co-Chair of the National Welfare Rights Union was also a member of the League. Kramer was crystal clear on the question of women in the League's leadership. Says Kramer: "We endured a lot of name-calling and had to fight male supremacy. Some would call us the IWW-"Ignorant Women of the World". I was thought of as one of the irouchiest women. We thought that women should have been on the executive board of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers."

Contrast this statement to the late Safiya Burkhari's views on how women fared in the BPP. While Burkhari was highly critical of the male chauvinism that was rampant in the BPP, she does not completely dismiss the organization. Said Burkhari: "The simple fact that the Black Panther Party had the courage to address the question in the first place was a monumental step forward. In a time when the other nationalist organizations were defining the role of women as barefoot and pregnant and in the kitchen, women in the Black Panther Party were working right alongside men, being assigned sections to organize just like the men, and receiving the same training as the men."

Abu-Jamal's We Want Freedom is a must read for all Black youth and the oppressed.

Toronto-based journalist and radio producer Norman (Otis) Richmond can be heard on Diasporic Music, Thursdays, 8 p.m. to 10 p. m., Saturday Morning Live, Saturdays, 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. and From A Different Perspective,Sundays, 6 p.m. to 6:30 p.m. on CKLN-FM 88.1 and on the internet at www.ckln.fm. He can be reached by phone at 416-595-5068 Ext 2372 or by e-mail at norman@ckln.fm

Mumia Abu-Jamal's latest work, We Want Freedom: A Life in The Black

Panther Party (South End Press, 2004), made me reflect on my political life.I came of age, politically, about the same time as Abu-Jamal. I participated in forming several organizations in the 1960s and '70s. One,the Detroit-based League of Revolutionary Black Workers, while not as well known as the Black Panther Party (BPP), was just as important. One of Abu-Jamal's quotes made me pause and take a deep breath because it hit the

nail on the head.

He writes: "To the average Panther, even though he worked daily in the ghetto communities of North America, his thoughts were usually on

something larger than himself. It meant being part of a worldwide movement against U.S. imperialism, White supremacy, colonialism and corrupting capitalism. We felt as if we were part of the peasant armies of Vietnam,the fedayeen in Palestine, the students strumming in the streets of Paris,and the disposed of Latin America."

I can remember being laughed at by some small-minded people because they felt I identified too much with Africa. My mother used to call me whenever Ho Chi Minh of Vietnam or Mao Zedong of China came on the news by saying,"Norman, your president is on television."

El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz's (Malcolm X) "Message to the Grassroots"

speech had a profound impact on my worldview. This speech was released on an album shortly after his death in the mid-1960s. When Malcolm talked about Afghanistan, Algeria, Burma, the Congo, Cuba, Pakistan, India, Indonesia, Kenya and Korea, I wanted to know everything about those far away places. During this same speech he went on to discuss the French and Russian Revolutions. I began to wonder: "Why don't they teach us about these places and events in school?"

The conditions of African people in the North and the South of the United States made me, and many of my peers, rage. We also discovered that millions of other Africans all over the world were in the same boat. While Abu-Jamal joined the BPP, I became a member of the League. The BPP and the League had many things in common, as well as some significant differences. The League's leadership, like the BPP, embraced Marxism-Leninism,Internationalism and Pan-Africanism; while most of the rank and file embraced revolutionary nationalism. However, the leadership of both groups and the rank and file shared a mutual hatred of U.S. Imperialism. The League addressed the question of cultural nationalism. The BPP and the

League were like political Siamese twins on this question. Both maintained that Blackness was necessary but not sufficient. While both organizations were fiercely internationalist, they differed on which class would lead the Black revolution. Both groups had films about their activities and both came up short on their treatment of women.

Both opposed the Vietnam War. In 1971, when Huey P. Newton, co-founder of the BPP was released from prison in California, his first act was to offer troops to fight in Vietnam on the side of the Vietnamese people. On August 29, 1970 Newton wrote “In the spirit of international revolutionary solidarity the Black Panther Party hereby offers to the National Liberation Front and Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam an undetermined number of troops to assist you in you fight against American imperialism. It is appropriate for the Black Panther Party to take this action at this time in recognize of the fact that your struggle is also our struggle, for we recognize that our common enemy is the American imperialist who is the leader of international bourgeois

domination.”

When General Baker, a central leader of the League, was drafted in 1964 he refused to heed Uncle Sam's call and created a lot of drama for the ruling elite. First, he wrote a letter to the draft board denouncing the war. Then, the organization he had belonged to before joining the League decided to protest his induction. They put out leaflets and press announcements stating that 50,000 Blacks would show up at the Wayne County Induction Center when Baker had to report. Only eight demonstrators were there, but the threat of mass action had convinced the U.S. army to find Baker "unsuitable" for service. Baker's position became the League's.

While the BPP held the lumpen proletariat up as the leaders of the Black revolution, the League maintained the Black working class was the natural leaders or vanguard of that struggle. The lumpen proletariat (directly translated: rag-proletariat) - a term used by Marxists - included prostitutes, beggars and homeless people.

Both groups were the subjects of films. Mario and Melvin Van Peebles'

film, Panther, was a fairer treatment of the group than most expected. The League's film, Finally Got The News, was a major breakthrough. While others created most of the films about the BPP, the League had complete control of Finally Got The News. John Watson, a central leader of the group, was largely responsible for this film.

How did women fare in the BPP and the League? On this question the BPP came out better than the League. The BPP at least had women on their central committee. The League had none. Marian Kramer, the co-Chair of the National Welfare Rights Union was also a member of the League. Kramer was crystal clear on the question of women in the League's leadership. Says Kramer: "We endured a lot of name-calling and had to fight male supremacy. Some would call us the IWW-"Ignorant Women of the World". I was thought of as one of the irouchiest women. We thought that women should have been on the executive board of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers."

Contrast this statement to the late Safiya Burkhari's views on how women fared in the BPP. While Burkhari was highly critical of the male chauvinism that was rampant in the BPP, she does not completely dismiss the organization. Said Burkhari: "The simple fact that the Black Panther Party had the courage to address the question in the first place was a monumental step forward. In a time when the other nationalist organizations were defining the role of women as barefoot and pregnant and in the kitchen, women in the Black Panther Party were working right alongside men, being assigned sections to organize just like the men, and receiving the same training as the men."

Abu-Jamal's We Want Freedom is a must read for all Black youth and the oppressed.

Toronto-based journalist and radio producer Norman (Otis) Richmond can be heard on Diasporic Music, Thursdays, 8 p.m. to 10 p. m., Saturday Morning Live, Saturdays, 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. and From A Different Perspective,Sundays, 6 p.m. to 6:30 p.m. on CKLN-FM 88.1 and on the internet at www.ckln.fm. He can be reached by phone at 416-595-5068 Ext 2372 or by e-mail at norman@ckln.fm

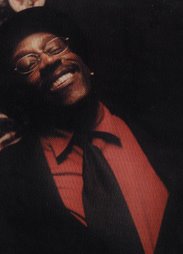

Curtis Mayfield: The Gentle Genius

By Norman Otis Richmond

Today when you think about the music of Chicago you’ll think of R.Kelly, Common, and of course Kanye West. The controversial West has continued to keep his name in the news by criticizing U.S. president George W. Bush for his inaction around Hurricane Katrina, or making good music. Chicago has also produced other Black musical giants like Mahalia Jackson, Jerry Butler and Curtis Mayfield. The multi-platinum recording artist and producer Kanye West sampled Mayfield’s “Move On Up” for his smash single “Touch The Sky.” Mayfield continues to influence popular music in North America and around the globe.

Mayfield joined the ancestors on December 26th 1999 at the age of 57. He commanded respect. His body of work has earned him a special place in African, American and world history. In a sense, Mayfield was a true "star in the ghetto." For whatever reason, he was never the darling of the mainstream, but African people from Cape Town to Nova Scotia loved him and his music madly. He was embraced by the hip-hop generation, millions in

Africa, and Bob Marley, Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer when they formed their group the Wailers.

Marley gives part of the writing credit for the song "One Love" to

Mayfield. “Here ain’t no room for the hopeless sinner/ Who would hurt all mankind just to save his own,” is from the pen of Mayfield. Marley lifted these lyrics from "People Get Ready.” Death row political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal acknowledges Mayfield in his book Live From Death Row. Says Abu-Jamal, "to elder Curtis Mayfield , whose sweet rebel songs echoed

across America & helped many a Panther pass the day, singing, "We’re a winner, and never let anybody say that y’all can’t make it, ‘cuz them people’s mind is in yo’ way."

Mayfield, who was born on June 3, 1942, burst on the scene as one of the Impressions in 1958. He sang background vocals and played guitar on the hit "For Your Precious Love." Jerry Butler sang lead on the song. The group disbanded for a time when Mayfield joined Butler as his guitarist and songwriter. Mayfield co- wrote "He Will Break Your Heart,” "Need to Belong to Someone" and "Find Yourself Another Girl." In 1961 Mayfield rejoined the Impressions as their lead singer and chief songwriter. They recorded "Gypsy Woman" for ABC Paramount and the rest is

history.

Butler maintains that he told Mayfield to write about his own reality and to forget the fantasy world. Mayfield's "Gypsy Woman" was inspired by a cowboy movie. Mayfield’s last fantasy song was "Minstrel and Queen." He soon began to write songs like "I’m So Proud," "Keep On Pushing," "People Get Ready," "Meeting Over Yonder" and "We’re A Winner." Following further hits with the Impressions (including,” Fool For Youm," "This Is My Country"

and the classic "Choice of Colors"), Mayfield decided to begin a solo career in 1970.

Despite the fact that Mayfield had distinguished himself as a recording artist, producer, songwriter and entrepreneur (he started his own label Curtom Records in 1968), there was still no guarantee that he could make it as a solo act. His first solo effort Curtis proved that he had the right stuff. "The Gentle Genius" soon became the "King of the soundtrack" after he composed the music for the film Superfly. The success of Superfly led to soundtracks for Sparkle, Let’s Do It Again, Claudine and Short Eyes.

One of the few "white spots" on Mayfield’s resume is the fact that he violated the cultural boycott of South Africa and performed there. He redeemed himself with the anti-apartheid movement when he apologized and vowed not to return until power was in the hands of the people.

Like many Black music makers, Mayfield never finished high school. He dropped out when he was 16. He did so only because an opportunity came up that he could join the Impressions. His mother allowed him to join the group with the proviso that he continue to study. Butler said Mayfield had one of the biggest libraries he’d ever seen. Blue Lovett of the Manhattans remembers Mayfield always reading a book backstage and not wasting time. Gladys Knight and the Pips, The Staple Singers, Rod Stewart,

Steppenwolf, Elton John, Herbie Hancock, UB40 , The Jam , Bruce

Springsteen, Eric Clapton, Lauryn Hill, Public Enemy and Ice T, are just a few of the diverse range of artists to have acknowledged Mayfield’s considerable musical talents and recorded his songs.

While Mayfield supported Dr. Martin Luther King and the Reverend Jesse Jackson, he visited Angela Davis in prison, "at her request," he once pointed out to this writer. He performed a cappella at a "Free Huey P. Newton" rally in Oakland along with the two other Impressions, Fred Cash and Sam Gooden. He is also acknowledged by Malcolm X’s daughter Ilyasah Shabazz in her book Growing Up X.

Mayfield was paralyzed in a 1990 accident in which he was struck by a rig that toppled while he was doing a benefit concert in Brooklyn. Even this could not keep Mayfield down. In 1993 Shanachie Records released People Get Ready: A Tribute To Curtis Mayfield with artists Jerry Butler, Don Covey, Steve Cropper, Huey Lewis & the News, Vernon Reid, David Sanborn,

Bunny Wailer and others. In 1994, Warner Bros. released All Men Are Brothers: A Tribute to Curtis Mayfield. This CD featured Mayfield’s compositions preformed by Eric Clapton, Aretha Franklin, Whitney Houston, The Isley Brothers, Elton John and the Sounds of Blackness, B.B. King, Gladys Knight, Branford Marsalis and the Impressions, Stevie Wonder and others. Among the "others" was a group called the Repercussions and Curtis

Mayfield. This song was Mayfield’s return to the world of recording.

Mayfield recorded his last album A New World Order in 1996. The album earned him a Grammy nomination and was used in Spike Lee’s film Get on the Bus. Nelson George pointed out that Mayfield balanced art and business and romance and revolution. Sam Cooke was Mayfield’s role model as an African American entrepreneur and message music maker. Cooke wrote and sang” A

Change Is Gonna Come." Mayfield, in my humble opinion, took Cooke’s ideas to the next level. A change did come with Mayfield.

The Gentle Genius wrote love songs and social commentary. His love songs were always a cut above the rest and were respectful of women. His message songs also represented his search for answers to the problems confronting humanity. The quietly spoken musician went on to explain that he also tried to avoid preaching at his audience. "With all respect, I'm sure that

we have enough preachers in the world. Through my way of writing I was capable of being able to say these things and yet not make a person feel as though they're being preached at."

Today when you think about the music of Chicago you’ll think of R.Kelly, Common, and of course Kanye West. The controversial West has continued to keep his name in the news by criticizing U.S. president George W. Bush for his inaction around Hurricane Katrina, or making good music. Chicago has also produced other Black musical giants like Mahalia Jackson, Jerry Butler and Curtis Mayfield. The multi-platinum recording artist and producer Kanye West sampled Mayfield’s “Move On Up” for his smash single “Touch The Sky.” Mayfield continues to influence popular music in North America and around the globe.

Mayfield joined the ancestors on December 26th 1999 at the age of 57. He commanded respect. His body of work has earned him a special place in African, American and world history. In a sense, Mayfield was a true "star in the ghetto." For whatever reason, he was never the darling of the mainstream, but African people from Cape Town to Nova Scotia loved him and his music madly. He was embraced by the hip-hop generation, millions in

Africa, and Bob Marley, Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer when they formed their group the Wailers.

Marley gives part of the writing credit for the song "One Love" to

Mayfield. “Here ain’t no room for the hopeless sinner/ Who would hurt all mankind just to save his own,” is from the pen of Mayfield. Marley lifted these lyrics from "People Get Ready.” Death row political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal acknowledges Mayfield in his book Live From Death Row. Says Abu-Jamal, "to elder Curtis Mayfield , whose sweet rebel songs echoed

across America & helped many a Panther pass the day, singing, "We’re a winner, and never let anybody say that y’all can’t make it, ‘cuz them people’s mind is in yo’ way."

Mayfield, who was born on June 3, 1942, burst on the scene as one of the Impressions in 1958. He sang background vocals and played guitar on the hit "For Your Precious Love." Jerry Butler sang lead on the song. The group disbanded for a time when Mayfield joined Butler as his guitarist and songwriter. Mayfield co- wrote "He Will Break Your Heart,” "Need to Belong to Someone" and "Find Yourself Another Girl." In 1961 Mayfield rejoined the Impressions as their lead singer and chief songwriter. They recorded "Gypsy Woman" for ABC Paramount and the rest is

history.

Butler maintains that he told Mayfield to write about his own reality and to forget the fantasy world. Mayfield's "Gypsy Woman" was inspired by a cowboy movie. Mayfield’s last fantasy song was "Minstrel and Queen." He soon began to write songs like "I’m So Proud," "Keep On Pushing," "People Get Ready," "Meeting Over Yonder" and "We’re A Winner." Following further hits with the Impressions (including,” Fool For Youm," "This Is My Country"

and the classic "Choice of Colors"), Mayfield decided to begin a solo career in 1970.

Despite the fact that Mayfield had distinguished himself as a recording artist, producer, songwriter and entrepreneur (he started his own label Curtom Records in 1968), there was still no guarantee that he could make it as a solo act. His first solo effort Curtis proved that he had the right stuff. "The Gentle Genius" soon became the "King of the soundtrack" after he composed the music for the film Superfly. The success of Superfly led to soundtracks for Sparkle, Let’s Do It Again, Claudine and Short Eyes.

One of the few "white spots" on Mayfield’s resume is the fact that he violated the cultural boycott of South Africa and performed there. He redeemed himself with the anti-apartheid movement when he apologized and vowed not to return until power was in the hands of the people.

Like many Black music makers, Mayfield never finished high school. He dropped out when he was 16. He did so only because an opportunity came up that he could join the Impressions. His mother allowed him to join the group with the proviso that he continue to study. Butler said Mayfield had one of the biggest libraries he’d ever seen. Blue Lovett of the Manhattans remembers Mayfield always reading a book backstage and not wasting time. Gladys Knight and the Pips, The Staple Singers, Rod Stewart,

Steppenwolf, Elton John, Herbie Hancock, UB40 , The Jam , Bruce

Springsteen, Eric Clapton, Lauryn Hill, Public Enemy and Ice T, are just a few of the diverse range of artists to have acknowledged Mayfield’s considerable musical talents and recorded his songs.

While Mayfield supported Dr. Martin Luther King and the Reverend Jesse Jackson, he visited Angela Davis in prison, "at her request," he once pointed out to this writer. He performed a cappella at a "Free Huey P. Newton" rally in Oakland along with the two other Impressions, Fred Cash and Sam Gooden. He is also acknowledged by Malcolm X’s daughter Ilyasah Shabazz in her book Growing Up X.

Mayfield was paralyzed in a 1990 accident in which he was struck by a rig that toppled while he was doing a benefit concert in Brooklyn. Even this could not keep Mayfield down. In 1993 Shanachie Records released People Get Ready: A Tribute To Curtis Mayfield with artists Jerry Butler, Don Covey, Steve Cropper, Huey Lewis & the News, Vernon Reid, David Sanborn,

Bunny Wailer and others. In 1994, Warner Bros. released All Men Are Brothers: A Tribute to Curtis Mayfield. This CD featured Mayfield’s compositions preformed by Eric Clapton, Aretha Franklin, Whitney Houston, The Isley Brothers, Elton John and the Sounds of Blackness, B.B. King, Gladys Knight, Branford Marsalis and the Impressions, Stevie Wonder and others. Among the "others" was a group called the Repercussions and Curtis

Mayfield. This song was Mayfield’s return to the world of recording.

Mayfield recorded his last album A New World Order in 1996. The album earned him a Grammy nomination and was used in Spike Lee’s film Get on the Bus. Nelson George pointed out that Mayfield balanced art and business and romance and revolution. Sam Cooke was Mayfield’s role model as an African American entrepreneur and message music maker. Cooke wrote and sang” A

Change Is Gonna Come." Mayfield, in my humble opinion, took Cooke’s ideas to the next level. A change did come with Mayfield.

The Gentle Genius wrote love songs and social commentary. His love songs were always a cut above the rest and were respectful of women. His message songs also represented his search for answers to the problems confronting humanity. The quietly spoken musician went on to explain that he also tried to avoid preaching at his audience. "With all respect, I'm sure that

we have enough preachers in the world. Through my way of writing I was capable of being able to say these things and yet not make a person feel as though they're being preached at."

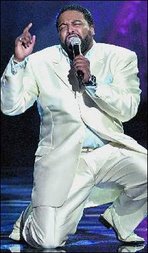

LEONARD PITTS: The lost art of singing 'baby, please'

BY LEONARD PITTS JR.

One day, maybe 20 years ago, I ran into Eddie Levert. Eddie, a charter member of the legendary O'Jays, is one of the greats, a singer of thunderous power. Back then, his son Gerald was just starting out as a professional singer, but already people were remarking how much he sounded like his father.

"You better look out," I told Ed. "He's gaining on you."

"Aw, don't tell that boy that," growled Eddie. "It'll go to his head."

For all his feigned indignation, he couldn't hide his pride. You saw it in him whenever they performed together, the son mimicking dance steps he grew up watching from backstage, or egging the father on with vocal dives and climbs and barrel rolls straight from the old man's own playbook.

So my first thought was of Eddie last week when the news came that Gerald had died of an apparent heart attack at the absurd age of 40. I can't imagine what it must be like to bury your son. Frankly, I don't want to know.

Gerald Levert's death wasn't big news in every neighborhood; he was a black R&B singer with little if any profile on white pop radio. But if you are black and of a certain age, it was the kind of bulletin that made you pull over the car.

We live in an era where music is largely impersonal, a cut-and-paste, machine-tooled artifice. Moreover, we live in an era where black music in particular is often a police blotter or a sex act or a product placement, but, less frequently, a love song. Still, some of us remember when black music was about soul, and soul was about truth -- particularly the truth of How It Is between women and men.

We used to call them begging songs -- "baby, baby please songs" -- for how they promised moon and stars to a woman if she would just give you the time of day, or pleaded with breaking voice and teary eyes for another chance after you fooled around and hurt her. Truth to tell, they weren't just songs; they were relationship how-to manuals. And Gerald sang them like his father's son: "Baby," "Hold On to Me," "Mr. Too Damn Good," "Made to Love Ya."

In him, you heard echoes of soul that came before, echoes of Eugene Record of the Chi-Lites asking, "Have You Seen Her?" and Lou Rawls vowing "You'll Never Find Another Love Like Mine," and Wilson Pickett promising good loving "In The Midnight Hour." You heard the ghost of Luther Vandross singing "Here and Now," Ray Charles swearing "I Can't Stop Loving You," and Barry White, smooth and chocolate like a human Dove Bar, saying, "I've Got So Much to Give."

These days, black music produces fewer songs that cherish women. Oh, there are plenty of sex songs -- plenty "I love your butt" songs. But "baby, please" is becoming a lost art.

I'm reminded of a talk I had with my middle son a few years ago. The Temptations had come on the radio singing "Ain't Too Proud to Beg," David Ruffin swearing to sleep on the woman's doorstep if she would just give him another chance. My son shook his head. Didn't matter how bad he was hurting or how much wrong he had done, he said, he could never sing a song like that. As far as he was concerned, he would always be too proud to beg.

I told him that sometimes begging is the best part. I told him that sometimes making up justifies breaking up. I told him that love requires vulnerability. He could not be convinced and, after a while, I stopped trying.

Me, I think things were better in black communities when there was more "baby, please" on the radio, when we held one another and sheltered one another from the vicissitudes of life. But those days are going. Every singer I referenced above has died within the last three years. And now, Gerald Levert has died, too.

I saw him in concert last year. At one point he came out into the audience and women went crazy, flying at him, wrapping themselves around him with a need deeper than sex. Baby, hold on to me, he sang. And boy, they did.

My son doesn't know what he's missing.

LEONARD PITTS JR. is a columnist for the Miami Herald, 1 Herald Plaza, Miami, Fla. 33132. Write to him at lpitts@miamiherald.com.

One day, maybe 20 years ago, I ran into Eddie Levert. Eddie, a charter member of the legendary O'Jays, is one of the greats, a singer of thunderous power. Back then, his son Gerald was just starting out as a professional singer, but already people were remarking how much he sounded like his father.

"You better look out," I told Ed. "He's gaining on you."

"Aw, don't tell that boy that," growled Eddie. "It'll go to his head."

For all his feigned indignation, he couldn't hide his pride. You saw it in him whenever they performed together, the son mimicking dance steps he grew up watching from backstage, or egging the father on with vocal dives and climbs and barrel rolls straight from the old man's own playbook.

So my first thought was of Eddie last week when the news came that Gerald had died of an apparent heart attack at the absurd age of 40. I can't imagine what it must be like to bury your son. Frankly, I don't want to know.

Gerald Levert's death wasn't big news in every neighborhood; he was a black R&B singer with little if any profile on white pop radio. But if you are black and of a certain age, it was the kind of bulletin that made you pull over the car.

We live in an era where music is largely impersonal, a cut-and-paste, machine-tooled artifice. Moreover, we live in an era where black music in particular is often a police blotter or a sex act or a product placement, but, less frequently, a love song. Still, some of us remember when black music was about soul, and soul was about truth -- particularly the truth of How It Is between women and men.

We used to call them begging songs -- "baby, baby please songs" -- for how they promised moon and stars to a woman if she would just give you the time of day, or pleaded with breaking voice and teary eyes for another chance after you fooled around and hurt her. Truth to tell, they weren't just songs; they were relationship how-to manuals. And Gerald sang them like his father's son: "Baby," "Hold On to Me," "Mr. Too Damn Good," "Made to Love Ya."

In him, you heard echoes of soul that came before, echoes of Eugene Record of the Chi-Lites asking, "Have You Seen Her?" and Lou Rawls vowing "You'll Never Find Another Love Like Mine," and Wilson Pickett promising good loving "In The Midnight Hour." You heard the ghost of Luther Vandross singing "Here and Now," Ray Charles swearing "I Can't Stop Loving You," and Barry White, smooth and chocolate like a human Dove Bar, saying, "I've Got So Much to Give."

These days, black music produces fewer songs that cherish women. Oh, there are plenty of sex songs -- plenty "I love your butt" songs. But "baby, please" is becoming a lost art.

I'm reminded of a talk I had with my middle son a few years ago. The Temptations had come on the radio singing "Ain't Too Proud to Beg," David Ruffin swearing to sleep on the woman's doorstep if she would just give him another chance. My son shook his head. Didn't matter how bad he was hurting or how much wrong he had done, he said, he could never sing a song like that. As far as he was concerned, he would always be too proud to beg.

I told him that sometimes begging is the best part. I told him that sometimes making up justifies breaking up. I told him that love requires vulnerability. He could not be convinced and, after a while, I stopped trying.

Me, I think things were better in black communities when there was more "baby, please" on the radio, when we held one another and sheltered one another from the vicissitudes of life. But those days are going. Every singer I referenced above has died within the last three years. And now, Gerald Levert has died, too.

I saw him in concert last year. At one point he came out into the audience and women went crazy, flying at him, wrapping themselves around him with a need deeper than sex. Baby, hold on to me, he sang. And boy, they did.

My son doesn't know what he's missing.

LEONARD PITTS JR. is a columnist for the Miami Herald, 1 Herald Plaza, Miami, Fla. 33132. Write to him at lpitts@miamiherald.com.

Donald Ray Johnson: Transplanted Blues Man

By Norman (Otis) Richmond

There is more than oil in Calgary, Alberta. Alberta is producing blues as well. Down home blues is alive and kickin’ in the Great White North.

Donald Ray Johnson has dropped his fourth blues CD; Travelin’ Man, a self produced album featuring eight cover versions of fallen R & B legends such as Little Milton Campbell, Johnnie Taylor and Tyrone Davis, and four original compositions.

Johnson pointed out in a recent telephone interview: “The Travelin’ Man

album is very special to me for many reasons. We lost quite a few of the legends I’ve admired over the years: Ray Charles, Tyrone Davis, Johnnie Taylor and Little Milton. We covered tunes by three of these legends on this project. Tyrone Davis’ “Sugar Daddy”, Little Milton’s “If Walls Could Talk” and Johnnie Taylor’s “Last Two Dollars.”

Saxophonist P.J. Perry, a Canadian icon, joins Johnson on “Last Two Dollars”.

“Me & Jack Daniels” and “Apple Tree” are from the pen of Johnson and

the only gospel gem on this effort is from his daughter Panzie, is a songwriter/performer who toured for 12 years with Stevie Wonder. The title track was written by Chicago guitarist, Maurice John Vaughn. Vaughn also took CD cover photo in France.

“Me & Jack Daniels” and two other tracks, “Yonder Wall” and the Lowell Fulsom- penned “Reconsider” was recorded in France with French musicians. Elmore James’, “Yonder Wall”, is updated by Johnson with a funky backdrop and the mentioning of the Iraqi war.

There are those who may say Johnson is getting “too political” on this track. Recall that James’ talked about the war in Korea and Freddy King’s version mentioned the war in Vietnam. Johnson has merely brought “Yonder Wall” into the 21st century.

Many of today’s blues admirers want to freeze the blues into a certain historical period. African Canadian blues artists like Johnson, Harrison Kennedy and Diana Braithwaite do not necessarily follow this model.

Check Johnson’s rendition of Willie Nelson’s “Always on My Mind”, which is a great addition to this CD. Nelson has long been admired by Black artists. Ray Charles included Nelson’s “Always on My Mind” on his CD of his favorite songs of all time. It must be mentioned that Nelson’s latest CD, Countryman ,is reggae. Nelson is a Euro-American “herbs man”.

Johnson was born in Bryan, Texas and moved to California, after completing high school. He took an early interest in music, as did his older sister, Janice Marie. They sang in church and at family functions. At age 7, Johnson became interested in playing the

drums, beating on whatever he could get his hands on.

In 1961 he was introduced to high school band director, Waymond Webster, who taught him to play “Traps." (The drum set).At age 14, he began his professional career with blues piano legend, Nat Dove. Throughout his teens, Johnson played with the two local bluesmen based in Bryan. Organist Joe Daniels and Guitarist Lavernis Thurman.

“We played a live radio show every Saturday night." Johnson joined the U.S. Navy and served aboard the aircraft carrier, USS Bon Homme Richard. After two tours in Southeast Asia (Viet Nam), he was honorably discharged, after his discharge Johnson relocated to San Diego.

While working “house band " at the Downtown Hustlers Club, Johnson met quite a few of the L.A.- based blues & R&B artists including Lowell Fulsom, Bobby Womack, and Pee Wee Crayton.

In early 1970, he was called to play weekends in LA with Phillip Walker, by long time friend Nat Dove, who now lived in LA. Some 29 years later the relationship with the Phillip Walker Band still exists.

In 1971, Johnson moved to LA to work with the Joe Houston big band, backing some of the west coast’s top blues artists. While trying to find a weekend gig, he met songwriter/ producer, Perry Kibble, who was in the process of developing a group that featured the talents of two young African American women, (bassist, Janice Marie Johnson & guitarist Carlita Durhan). They later became known as " A Taste Of Honey ". In 1979, this band was the first African - American Band to win and be presented with the "Grammy Award" for "Best New Artist".

Once upon a time the voices of Lou Rawls, Barry White and, in recent memory Michael Shawn McCary of the vocal group, Boyz II Men boomed all over Black and Top 40 radio stations. Baritone and bass voices are as scarce as hen’s teeth in the 21st century on what is now called urban radio.

Why are radio- friendly baritone and bass voices no longer a welcome on urban radio? Are these sounds too “Black and strong” for today’s urban dwellers? Johnson is in the tradition of Rawls. His voice is deep, rich and sweet as Blackstrap molasses.

The Toronto Blues Society has heeded the call for a return to great voices. Johnson has been nominated-along with Harrison Kennedy, John Mays, Jim Byrnes and David Clayton Thomas- for a 2006 Maple Blues Award. It is great to see a transplanted blues man receive his due in his adopted home land. For more information about Johnson and his music you can visit him in cyberspace www.donaldray.com/

Check out Norman Otis Richmond’s new music blogspot-- http://normanrichmond.blogspot.com/

There is more than oil in Calgary, Alberta. Alberta is producing blues as well. Down home blues is alive and kickin’ in the Great White North.

Donald Ray Johnson has dropped his fourth blues CD; Travelin’ Man, a self produced album featuring eight cover versions of fallen R & B legends such as Little Milton Campbell, Johnnie Taylor and Tyrone Davis, and four original compositions.

Johnson pointed out in a recent telephone interview: “The Travelin’ Man

album is very special to me for many reasons. We lost quite a few of the legends I’ve admired over the years: Ray Charles, Tyrone Davis, Johnnie Taylor and Little Milton. We covered tunes by three of these legends on this project. Tyrone Davis’ “Sugar Daddy”, Little Milton’s “If Walls Could Talk” and Johnnie Taylor’s “Last Two Dollars.”

Saxophonist P.J. Perry, a Canadian icon, joins Johnson on “Last Two Dollars”.

“Me & Jack Daniels” and “Apple Tree” are from the pen of Johnson and

the only gospel gem on this effort is from his daughter Panzie, is a songwriter/performer who toured for 12 years with Stevie Wonder. The title track was written by Chicago guitarist, Maurice John Vaughn. Vaughn also took CD cover photo in France.

“Me & Jack Daniels” and two other tracks, “Yonder Wall” and the Lowell Fulsom- penned “Reconsider” was recorded in France with French musicians. Elmore James’, “Yonder Wall”, is updated by Johnson with a funky backdrop and the mentioning of the Iraqi war.

There are those who may say Johnson is getting “too political” on this track. Recall that James’ talked about the war in Korea and Freddy King’s version mentioned the war in Vietnam. Johnson has merely brought “Yonder Wall” into the 21st century.

Many of today’s blues admirers want to freeze the blues into a certain historical period. African Canadian blues artists like Johnson, Harrison Kennedy and Diana Braithwaite do not necessarily follow this model.

Check Johnson’s rendition of Willie Nelson’s “Always on My Mind”, which is a great addition to this CD. Nelson has long been admired by Black artists. Ray Charles included Nelson’s “Always on My Mind” on his CD of his favorite songs of all time. It must be mentioned that Nelson’s latest CD, Countryman ,is reggae. Nelson is a Euro-American “herbs man”.

Johnson was born in Bryan, Texas and moved to California, after completing high school. He took an early interest in music, as did his older sister, Janice Marie. They sang in church and at family functions. At age 7, Johnson became interested in playing the

drums, beating on whatever he could get his hands on.

In 1961 he was introduced to high school band director, Waymond Webster, who taught him to play “Traps." (The drum set).At age 14, he began his professional career with blues piano legend, Nat Dove. Throughout his teens, Johnson played with the two local bluesmen based in Bryan. Organist Joe Daniels and Guitarist Lavernis Thurman.

“We played a live radio show every Saturday night." Johnson joined the U.S. Navy and served aboard the aircraft carrier, USS Bon Homme Richard. After two tours in Southeast Asia (Viet Nam), he was honorably discharged, after his discharge Johnson relocated to San Diego.

While working “house band " at the Downtown Hustlers Club, Johnson met quite a few of the L.A.- based blues & R&B artists including Lowell Fulsom, Bobby Womack, and Pee Wee Crayton.

In early 1970, he was called to play weekends in LA with Phillip Walker, by long time friend Nat Dove, who now lived in LA. Some 29 years later the relationship with the Phillip Walker Band still exists.

In 1971, Johnson moved to LA to work with the Joe Houston big band, backing some of the west coast’s top blues artists. While trying to find a weekend gig, he met songwriter/ producer, Perry Kibble, who was in the process of developing a group that featured the talents of two young African American women, (bassist, Janice Marie Johnson & guitarist Carlita Durhan). They later became known as " A Taste Of Honey ". In 1979, this band was the first African - American Band to win and be presented with the "Grammy Award" for "Best New Artist".

Once upon a time the voices of Lou Rawls, Barry White and, in recent memory Michael Shawn McCary of the vocal group, Boyz II Men boomed all over Black and Top 40 radio stations. Baritone and bass voices are as scarce as hen’s teeth in the 21st century on what is now called urban radio.

Why are radio- friendly baritone and bass voices no longer a welcome on urban radio? Are these sounds too “Black and strong” for today’s urban dwellers? Johnson is in the tradition of Rawls. His voice is deep, rich and sweet as Blackstrap molasses.

The Toronto Blues Society has heeded the call for a return to great voices. Johnson has been nominated-along with Harrison Kennedy, John Mays, Jim Byrnes and David Clayton Thomas- for a 2006 Maple Blues Award. It is great to see a transplanted blues man receive his due in his adopted home land. For more information about Johnson and his music you can visit him in cyberspace www.donaldray.com/

Check out Norman Otis Richmond’s new music blogspot-- http://normanrichmond.blogspot.com/

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)